To quote a favorite young lady of mine, “People suck.”

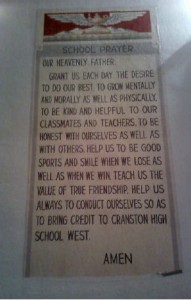

At Rhode Island’s Cranston High School West, student Jessica Ahlquist took issue with the banner hanging in the school labeled “School Prayer.” She successfully sued her state-funded public school to have a it removed. This was a classic textbook case of separation of church and state, and U.S. District Court Judge Ronald R. Lagueux even praised her for her courage in his written decision.

This was hardly judicial activism. Any high school civics student should have recognized that this was the inescapable outcome were this issue heard in any court in the land. Some might argue the law is wrong, but it’s hard to imagine anyone being surprised that it’s the law.

It might even be argued that had the school had the good sense to label the banner “School Pledge” and drop the Heavenly Father reference and the Amen that it would have been a completely legal banner. But they didn’t, and so it isn’t.

It might even be argued that had the school had the good sense to label the banner “School Pledge” and drop the Heavenly Father reference and the Amen that it would have been a completely legal banner. But they didn’t, and so it isn’t.

Yet it isn’t the loss of this banner that diminishes Christianity. It is the violent threats of retaliation against Ahlquist from other students. In what appears to be a woefully misguided sense of defending their religion, classmates are not only verbally insulting the young activist, but physically threatening her with assault and rape, both in this life and the next. Just a few of the things posted to Facebook and Twitter are listed below.

“May that little, evil athiest teenage girl and that judge BURN IN HELL!”

“I hope there’s lots of banners in hell when your rotting in there you atheist fuck #TeamJesus”

“If this banner comes down, hell i hope the school burns down with it!”

“U little brainless idiot, hope u will be punished, you have not win sh..t! Stupid little brainless skunk!”

“Fuck Jessica alquist I’ll drop anchor on her face”

“definetly laying it down on this athiest tommorow anyone else?”

“Nothing bad better happen tomorrow #justsaying #fridaythe13th”

“Let’s all jump that girl who did the banner #fuckthatho”

“”But for real somebody should jump this girl” lmao let’s do it!”

“Hmm jess is in my bio class, she’s gonna get some shit thrown at her”

“hail Mary full of grace @jessicaahlquist is gonna get punched in the face”

“When I take over the world I’m going to do a holocaust to all the atheists”

“gods going to fuck your ass with that banner you scumbag”

“if I wasn’t 18 and wouldn’t go to jail I’d beat the shit out of her idk how she got away with not getting beat up yet”

“nail her to a cross”

“We can make so many jokes about this dumb bitch, but who cares #thatbitchisgointohell and Satan is gonna rape her.”

I know kids can be stupid and cruel, but I can’t fathom that somehow this level of malevolence is being wielded in the defense of Christianity. Even assuming that somehow this was well intentioned, in so trying to save their religion they have made it considerably less. Ironically, atheists are often accused of unfairly conflating religion and violence. Yet these allegedly Christian students make a compelling case all on their own.

Young Jessica Ahlquist returns to school today for the first time since the ruling on the banner. Her morning Tweet suggests a high degree of optimism, or maybe hope. “time for school. Woot. #bestdayever,” I hope she’s right.

WWJD, indeed.