I am not an economist. However, for reasons I dare not delve into too deeply, my lady finds discussions of economics a turn-on. The downside is that now I not only have to compete with George Clooney and Toby Keith, but also with the likes of Ezra Klein and Brad DeLong. If one of them ever develops tech skills, I’m toast. In the meantime, “Get in line boys.”

I am not an economist. However, for reasons I dare not delve into too deeply, my lady finds discussions of economics a turn-on. The downside is that now I not only have to compete with George Clooney and Toby Keith, but also with the likes of Ezra Klein and Brad DeLong. If one of them ever develops tech skills, I’m toast. In the meantime, “Get in line boys.”

As I’ve written in this space before, one of the damnable things about macroeconomics is that it is so blastedly non-intuitive. Most of us are schooled or experienced in microeconomics (open systems), whether that be managing a household budget or running a business. Macro, or closed systems like the U.S. economy, work on a very different set of rules and have a very different set of control levers to work with. It’s abstruse stuff, and my hope is that maybe I can do a bit of the heavy lifting here, so some elements of macroeconomics make a little more sense.

Presidential hopeful Rick Perry made headlines this week for his statement that if the Fed decides to print more money, it should be seen as a treasonous act. Perry’s not alone here. While most politicians are distancing themselves from claiming it’s treasonous, many are advocating that the Fed should not take further actions like “Quantitative Easing” to increase the money supply.

So what does all that mean? Printing money out of thin air sure sounds like a dumb solution. Doesn’t that just make my hard-earned money worth less? How would that help the economy? These are all reasonable questions. Questions which I’ve been struggling to get my own non-economist head around by reading what actual economists are saying. The trouble is, folks like Matt Yglesias and Scott Sumner often write for an audience of fellow economic geeks. And it’s often damn hard to wade through the jargon to figure out the underlying principles at work. But I think I have a handle on it, and want to share my translation and understanding.

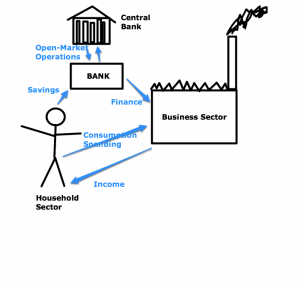

First, “printing money” is a euphemism. No actual currency gets produced. Rather, the Federal Reserve has a number of levers by which it can alter the supply of money. Think of the U.S economy as the proverbial pie. Each slice of pie represents a unit of money, like a dollar. Increasing the money supply doesn’t change the size of the pie, but it does change the size of the dollar (slice). If you carve the pie into more slices, then each slice has less in it. “Quantitative Easing” is one of the levers the Fed can use to increase the size of the money supply. And yes, the effect of this is to lessen the value of the dollar.

A weaker dollar seems like a bad thing. It offends the American sensibilities to think of anything about us as weak. But in cold economic terms, there are pluses and minuses to a devalued dollar. A weak dollar doesn’t translate to a weak economy. In fact, in our present situation, it could translate to a stronger one. But first, a word about… inflation.

Another term for devaluation is inflation, a word that also sounds bad. Inflation is especially troubling to those of us that lived through the 70’s and early 80’s where double-digit inflation was rampant. We also saw the economic collapse of Argentina, Zimbabwe, and other countries because of hyperinflation. But we need to remember that inflation is a lot like oxygen. Too little can be just as deadly as too much. Japan’s “lost decade” of the 1990’s was a period marked by very low inflation, economic recession, low productivity, and high unemployment. Sound familiar?

Inflation in America has been at historic lows for the last couple of years. The key is to find the sweet spot of around 3% and hold that. In many respects, this is what the Fed’s job is. It tries to maintain that small positive healthy inflation rate. It’s a balancing act. And an over-correction could send inflation spiraling in either direction. This is primarily what conservative fear at the moment. That an attempt to nudge inflation up will start a cascade reaction that will send us back to the 70’s. No one wants that. (Unless you’re invested long in polyester and hairspray commodities.)

But why is some inflation good, and why would a little extra be good right now?

In terms of the flow of money in an economy, the net effects of inflation in absolute dollars are a rise in the cost of goods, a rise in the cost of labor (wages), and a rise in value of assets (homes, stocks). Granted, these don’t always rise uniformly. Prices tend to rise ahead of wages, causing short term pain. But wages do follow suit, eventually making the inflation kind of a wash. Remember back in the early 80’s when getting a 10-15% annual raise was common?

What doesn’t change in a good way with inflation is cash. In other words, if you’re sitting on a lot of liquid assets, those assets become worth less. Who’s sitting on cash? Well, big corporations are sitting on over a $1 trillion, and of course banks have a lot of fixed cash assets, not the least of which are all the mortgages out there. If you’ve loaned out $100k at 4% for 30 years and inflation suddenly hits 5%, you’re losing money.

On the flip side, inflation would be great for consumers who are currently sitting on near record household debt. As an example, many people are currently underwater on their mortgages. Let’s say you owe $200k on a $175k house. Inflation doesn’t change the amount you owe, but it does increase the value of the property. So now you’re not underwater anymore. Further, if you have a low-interest home loan, a higher inflation rate suddenly makes that nearly free money. It doesn’t decrease your absolute debt, but it does decrease your relative debt, especially as your wages start to rise.

Finally, inflation also punishes people who are sitting on cash. As almost everyone has said since the economy went south in 2008, we need cash to flow to stimulate the economy. Think of money like the blood of the economy. To the body as a whole, it’s less important exactly how much blood you have, than that the blood you have is circulating vigorously through your system. The U.S. has an ample blood supply, but it’s currently pooled. We need to get it pumping, and inflation helps that.

There are also advantages to America relative to the world. A weaker dollar makes our goods cheaper to sell to other countries, and imported goods more expensive here. This is an immediate boon to exporting companies. However, given that we import a ridiculous portion of the goods bought in this country, it will drive the cost of those goods higher. The good news is that there will be less incentive to design, manufacture, and service goods overseas, and that would mean more jobs for Americans as jobs start to come back onshore. But again, that’s a short term pain for long term gain bargain.

Hopefully by now, you’re starting to think that maybe this whole printing money thing doesn’t sound quite so treasonous. Maybe you’re thinking it’s even worth a shot, or at least that it’s a perfectly reasonable tool to use. Ironically, Rick Perry himself believes it will have a positive effect on the economy.

Perry said the central bank’s leader would be committing a “treasonous” act if he decided to “print more money to boost the economy.” Such action, the governor told a crowd in Iowa, would amount to a political maneuver aimed at helping Obama win re-election.

Perry is explicitly saying that increasing the money supply would boost the economy. What he finds treasonous is only that he knows a better economy would help re-elect Obama. All of which brings us to why increasing the money supply is politically unpopular.

- It aids Obama’s re-election, so Republicans are opposed

- It hurts banks so they are opposed

- It hurts companies who have moved all their operations offshore, so they are opposed.

- It raises prices ahead of wages and new jobs, so in the short term, voters will be opposed.

- Voter anger and the resultant news cycles and Gallup polls will crucify incumbents, so they are opposed.

None of these reasons make increasing the money supply bad policy. They simply mean that this is a situation where the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. Unfortunately, the few are largely in charge of the policy. However, the beauty of the money supply is that changing it does not require Congressional approval. The Fed has the authority to act on its own. Although the Fed is largely populated with people from the financial industries who appear to be way more scared of large inflation than lack of it. But still, there is less of a barrier to action here than almost any other plan available.

Anything we do to fix the economy is going to cause some pain somewhere. Increasing the money supply is perhaps the most actionable thing we can try. It may be insufficient, and there are some risks involved. But dammit, let’s at least do something. I’m tired of our strategy being all hope and no change.